Australian Constitutions Act 1850 (UK)

Significance

This document is significant for all four Australian colonies established before the 1850s. The Assent original of the British Act of Parliament separating Victoria from New South Wales, and naming and providing a Constitution for the new Colony, it was signed by Queen Victoria on 5 August 1850.The New South Wales Parliament passed the necessary enabling legislation before separation took effect on 1 July 1851. This was formally the founding moment of the Colony of Victoria, its separation from New South Wales established by Section 1 of this Act.

This document was also important in its effects on the government of all four established colonies, New South Wales, Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania), South Australia and Western Australia.

For New South Wales, the Act not only reduced the territory of the government in separating Victoria from New South Wales, but provided for changes to government within New South Wales. It liberalised the franchise qualifications for the New South Wales Legislative Council (Section 4) and it empowered the Governor and the Legislative Council, with Britain's approval, to establish a Parliament of two Houses, either appointed or elected (Section 2).

For Van Diemen's Land, the Act authorised a number of important changes:

- creation of a Legislative Council with two-thirds of the members elected (Section 7)

- empowering the Governor, with the advice and consent of this Legislative Council, to make laws 'for the Peace, Welfare and good Government' of the Colony, with the proviso that such laws not be repugnant to the law of England (Section 14)

- laws in force when writs were issued for the election of the Legislative Council were to remain in force (Section 25)

- the new Legislative Council could make further provision for the administration of justice, including juries (Section 29)

- any Bill passed by the new Legislative Council could be reserved by the Lieutenant-Governor 'for the signification of Her Majesty's pleasure thereon' (Section 33).

The Legislative Council also received the power to prepare Bills for Royal Assent altering the constitution of the Legislative Council by varying the qualifications of electors and elected members. It could also present a Bill for Royal Assent to replace itself with a Legislative Council and 'House of Representatives' whose members might be appointed or elected (Section 32). The way was paved for creating a colonial version of the two chambers (the House of Lords and the House of Commons) of the Imperial Parliament.

Western Australia had just begun to receive convicts, and was thus subject to special provisions in Section 9 of the Act providing that, upon the petition of not less than one-third of the householders of the colony, and when the Colony ceased to depend on grants from the United Kingdom, a Legislative Council (to consist of members of whom two-thirds might be elected) could be established by the existing Council.

History

1.VictoriaThe Port Phillip District grew rapidly. By 1850 it was a wealthy region with a population of more than 70 000 and contained nearly six million sheep (two-fifths of the Australian total).

Throughout the 1840s the residents of the Port Phillip District agitated for independence from New South Wales. After the enactment of the New South Wales Constitution Act in 1842, they were granted the right to elect six of the 24 elected members of the Legislative Council of New South Wales. Despite this concession, an independence movement continued to petition the British government for Victoria's own representative government. They succeeded when this Act became law on 5 August 1850, and conferred on the colony a Constitution similar to that enjoyed by New South Wales since 1842, with a separate, partly elected Legislative Council (Section 2).

The news reached Victoria on 11 November 1850, and was celebrated along with the opening of the new Princes Bridge over the Yarra. Separation took effect on 1 July 1851.

2. New South Wales

In New South Wales this Act was criticised for insufficiently providing for local control of revenue, and for failing to give the Legislative Council full powers. The Act did not satisfy growing demands for self-government and a draft Constitution for New South Wales was prepared. This was submitted to Britain and amended, becoming part of the New South Wales Constitution Act and passed by the British Parliament in 1855.

3. Tasmania

In New South Wales and Victoria, where transportation of convicts virtually ceased after 1840, the Australian Constitutions Act was widely welcomed as providing processes of constitutional reform. The eventual goal for many was responsible government, with colonial premiers and ministries more closely resembling the British Prime Minister and ministries. The colonial governor's role would be broadly similar to that of the monarch in Britain – to commission as chief minister and thus head of government, whoever commanded a majority in the legislature. The immediate effect of this Act for Tasmania was partly representative government on the model in operation in New South Wales since 1842. In this model, the Governor remained, in an active and practical sense, the chief executive as well as the Vice-Regal representative in the Colony.

Continuing transportation of convicts from Britain meant 'responsible government' for the Island was a remote prospect in 1850. While anti-transportation agitation was part of public life in Van Diemen's Land from 1847, it is hard to detect much impact of this on the British Parliament.

In 1851 that situation changed. The discovery of extensive alluvial gold in Victoria from 1851 persuaded the British government that sending convicts to a Colony close to probably the richest goldfield in the world was bad policy. By 1850 the Tasmanian anti-transportation movement had developed into a crusade for 'social freedom', the phrase of prominent Launceston anti-transportationist, the Reverend John West. The crusade quality of this movement found expression at mass meetings in Van Diemen's Land and Victoria. It also produced a Federation Flag very similar to the present Australian ensign.

The Colonial Secretary in Britain, Sir John Pakington, on 14 December 1852 wrote to Lieutenant-Governor Denison, a resolute defender of transportation, foreshadowing its end. The Duke of Newcastle, Pakington's successor, confirmed the demise in a despatch of 22 February 1853, (CO 408/37). Cessation of transportation was confirmed by an Order-in-Council of 29 December 1853, which repealed an 1847 designation of Van Diemen's Land as a penal colony.

In December 1852 Pakington (and the following year his successor Newcastle) wrote to the governors of New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia encouraging them to draft constitutions under the 1850 Act. He suggested these embody a bicameral legislature with an elected Lower House, control over colonial waste lands (a prize hitherto retained by the British Parliament) and, in effect, responsible government. Here Denison perhaps showed himself a good loser. He wrote to Newcastle on 25 August 1853 requesting that Van Diemen's Land receive the same invitation. Newcastle agreed on 30 January 1854. However the Island was already on track to responsible government, and on 1 September 1853, Thomas Daniel Chapman moved in the Legislative Council for the introduction of a Bill which became the Constitution Act 1855.

4. Western Australia

At the time the Australian Constitutions Act was passed, Western Australia had just started receiving convicts with the first boatload arriving on 1 June 1850. There were thus special provisions in the Act for what was now the only penal colony in Australia, limiting rights to participation in government. Householders petitioned for greater representation in 1865 and although the petition was rejected, six additional members were added to the Council. In 1867 the Governor agreed to nominate those elected on an adult suffrage basis. When transportation ended in 1868 the provisions of Section 9 were fully implemented and a Legislative Council with two-thirds of its members elected was created in 1870.

When Western Australia moved to establish a bi-cameral legislature and responsible government in 1889, Section 32 of this 1850 Act meant the Bill had first to be agreed in the British Parliament, before being enacted as the Constitution Act 1890.

Sources

Townsley, WA, The Struggle for Self-Government in Tasmania, 1842–1856, Tasmanian Government Printer, 1951.

Waugh, John, The Rules: An Introduction to the Australian Constitutions, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1996.

Description

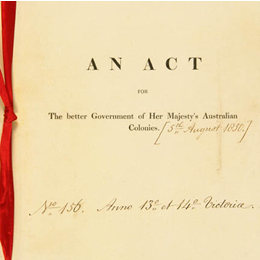

Printed in black ink on gatherings of off-white vellum leaves which are pierced with three holes in the left-hand margin and bound by a red silk tape passed through them and tied on the front cover.

Detail from the front cover of the Australian Constitutions Act 1850 (UK).

| Long Title: | An Act for the better Government of Her Majesty's Australian Colonies. |

| No. of pages: | 22 + cover (9 + cover shown here) |

| Medium: | Vellum |

| Measurements: | Each leaf approximately 8 inches x 12 inches |

| Provenance: | British Parliament, received in the Record Office 1850 |

| Features: | A comprehensive document affecting five colonies. |

| Location & Copyright: | House of Lords Record Office |

| Reference: | 13 & 14 Vic. No. 156 |